My Great-Grandmother Owned a Library

On World Book Day, I remember Mrs. Beretta who built a business from books.

I felt my great-grandmother’s presence on my morning walk, as sunlight turned the dog’s wispy fur silver. While planning my visit to the library later that day, Mrs. Beretta entered my restless mind. My mother's grandmother, of Italian heritage, had famously owned a library, a legacy the family remains deeply proud of. On World Book Day, I looked forward to, and felt grateful for a space where I could sit, read, and write without spending a penny. We are fortunate in this country to have libraries that are open to all, providing free access to knowledge, community, and opportunity. In that moment, it felt as though my great-grandmother had manifested to remind me of that privilege and to spark within me the same resilience and resourcefulness that defined her.

Mrs. Beretta's library was in The Hague, in the Netherlands, and the Art Deco buildings are still there. In her day, libraries were not free. They were private enterprises, run like small businesses. Widowed young, she had to work hard for a living. She had two boys, my grandad Peter and his little brother Arnold who had severe asthma.

Yet, she kept the family afloat. Before her husband's death, she had been a hatmaker, crafting beauty out of felt and ribbon. When she needed a new livelihood, she turned to books. People paid to sit in her ‘reading library’ or to take a book away for a time. Her business also sold stationery, offered printing and business cards, repairs to fountain pens, and bookbinding.

Her brother-in-law invested in the library to support his wife’s sister and her children, a Catholic thing to do. The shop was named after him – Oomens, in true 1920s fashion. At the time, women couldn’t secure bank loans. He placed an advert in the paper announcing the opening; we still have the clipping. I looked up the address of her first library on Google Maps. It’s a children’s clothing store now, in a stately neighbourhood near the palace.

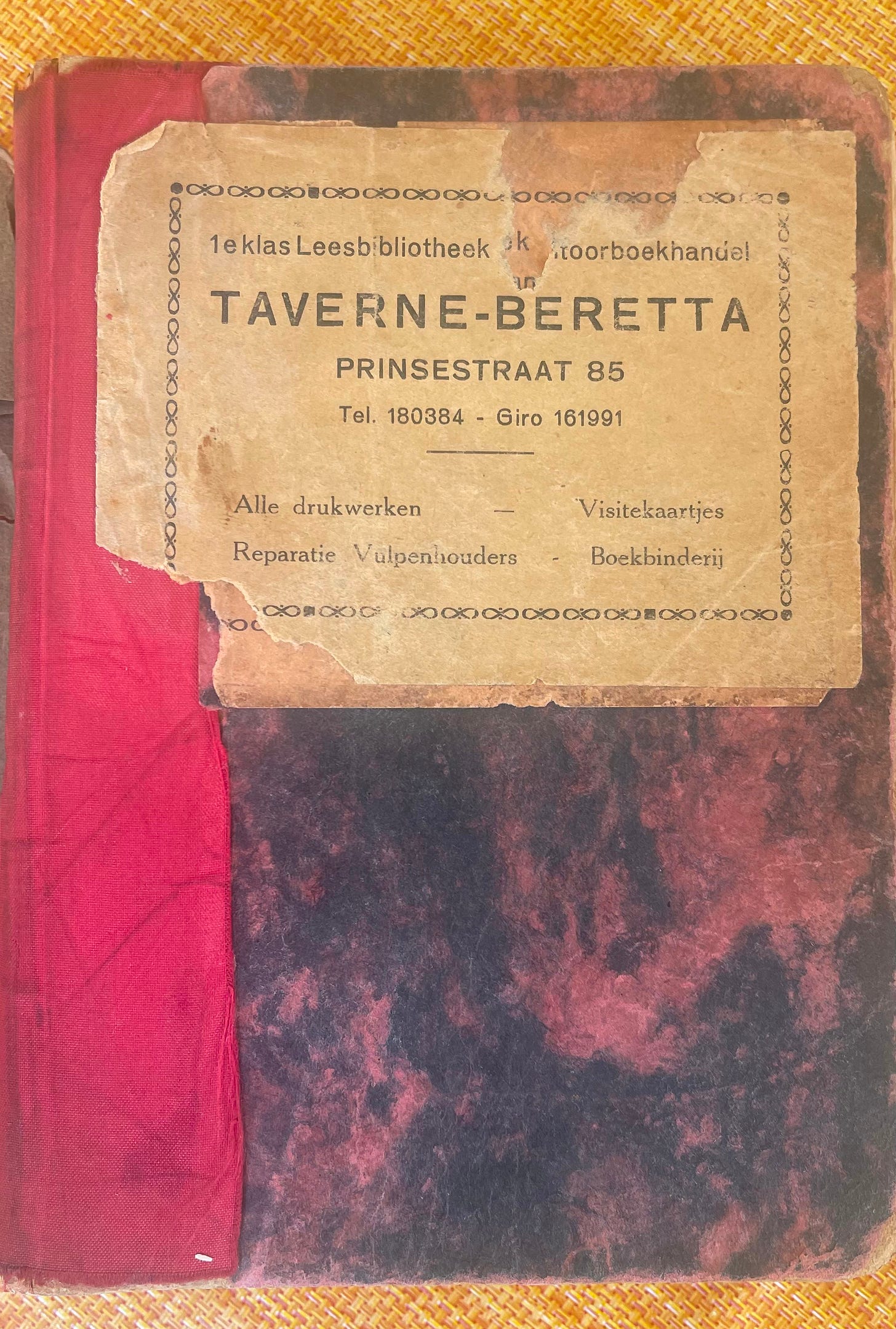

Later, the library would bear her own name, Taverne-Beretta (her deceased husband's name followed by her own) and open up in a different stately neighbourhood in the city centre, and again in a street next to a palace, Her Majesty’s ‘working palace’. I’d like to think that she must have been so proud to move into a much bigger shop, again near royalty. On my phone I look at a portrait of her sent by my mum, her granddaughter, in which she stares wistfully away from the camera with a huge updo. We have the same chin and Italian nose.

What would she think of libraries today? Would she marvel at the fact that anyone can walk in and borrow a book, for free? Or would she despair at how few children do? Studies from 2024 found that only one in three children in the UK read for pleasure. Only 34% of adults visited a public library in the previous 12 months, including those visiting for academic or paid work purposes. Published in 2024, a report found that 180 council-run libraries had either closed or been handed over to volunteer groups in the UK since 2016.

It’s easy to blame phones, games, streaming and attention spans. But how many people even know what libraries offer now? My dear friend, who leads strategy and policy at Leeds Libraries, often emphasises that libraries are more than just books. They are Warm Spaces. They offer free WiFi, job search support, film streaming, audiobooks, events and a sense of community. Again, all FREE!

And yet, funding is slashed year after year. So many people still turn to Amazon for something they could borrow. So many children are growing up in homes without books, never seeing the inside of a library at all. COVID is often blamed in articles, which makes me think about Mrs. Beretta living through war, through rationing, through times when words were all people had. Her library survived the Nazi occupation, even as her own sons hid in a broom cupboard while soldiers pounded on the door, dragging boys into forced service. My grandfather held his hand over his brother’s mouth to silence his wheezing. In the room next to them, the bookshelves stood undisturbed.

Among her belongings, we have a book from her library with a branded sticker that has since yellowed. The cover is plain, bound in red and black board, smelling faintly of cinnamon and dust. The book is a third in a series about a girl called Marijke, an orphan who is raised by her sisters and gets to go to college. The third and last book is about her travelling abroad while working as a nurse for a wealthy lady and meeting her son. Yes, they fall in love.

At the back of the book, I found pencilled return dates: 1947, 1948, 1949. Then nothing. I don’t know what happened in that moment, when the last person returned the book. The fate of Beretta’s Library remains unknown to me. Maybe the rise of free, state-run libraries made small lending businesses like hers obsolete. Maybe stories about girls who travel to meet wealthy husbands no longer captured readers' imaginations the way they once did. Maybe my glamorous grandmother just got old.

But I do know that a hundred years later, I sit in my own local library, drinking a free cup of coffee from the Warm Spaces initiative, tapping away at my laptop. Without spaces like these, where would we be?

On World Book Day, it’s easy to celebrate reading without thinking about the spaces that make it possible. Libraries will only survive when we use them. Borrow a book. Take your child. Tell a friend. Support the staff (who are all women, here in Hebden Bridge) who keep these spaces alive. Because once libraries disappear, they don’t come back.